Even without the intensities/overexcitabilities so common in our gifted population, kids can be overly emotional. What do I mean by overly emotional?

I mean that they:

- overreact to even mild stimuli; and/or

- base decisions on emotions rather than reason at a level inappropriate for their age; and/or

- engage in a level of emotionality that interferes with their ability to be happy/effective/have friends/be successful in school/home/religious/extracurricular activities.

Typing this list makes me realize I know a lot of adults like this as well!

Some of this can be a result of inappropriate expectations because of asynchronous development. Adults sometimes expect a child who can do math or read at a level far beyond their chronological age peers to behave at a higher level as well. That’s not reasonable.

At the same time, sometimes we don’t guide children in ways they need because we attribute behavior to giftedness (or any number of a host of reasons) and are hesitant to correct them.

Sometimes we confuse “reason” with “excuse.”

Sometimes, we love them so much, we can’t stand to see them hurting, and it’s hard to see beyond their hurt to evaluate the root cause objectively.

Whatever the reason(s), it’s a common issue worth exploring.

Supporting Overly Emotional Children with Peer Interaction: Reader Q & A

I received this question:

How can I support my child with being very sensitive (emotional) when things go differently or not interesting to him?

How can I help him with other kids not wanting to play with him?

How can I get him to express himself when others say mean things to him?

Note: Frequently I get questions from parents or teachers about their children and students. It’s frustrated me that I don’t have time to write back to everyone, and so I’ve decided to begin a “Reader Q & A” feature on the site. You can find all responses here.

If you have a question about your child, your student, best practices, or anything Giftedesque, shoot me an email or comment below, and we’ll see what we can do!

This question was really three separate questions, so I’m going to separate them out to respond.

Question 1: How can I support my child with being very sensitive (emotional) when things go differently or not interesting to him?

This is tricky because there’s a fine line between “support” and “enable.”

Support is when we walk kids through feelings they’re having and help them manage those feelings. Enabling is when we feed inappropriate emotional outbursts or responses by giving them too much attention or being too quick to cast blame on others or situations.

This question is aligned with the emotional intelligence skill of self-regulation. Self-regulation is the skill that allows people to realize that, while they may be feeling something, it’s not a good time or a good way to show it.

Kids aren’t the only ones who lack this skill. I mean, just look at Twitter.

Consider the discrepancy between the way the child is acting when confronted with these situations and a healthier way to react.

What is the child’s current response? What would be an ideal response that would be appropriate to expect in this circumstance?

During a calm time apart from this kind of stimuli, role play scenarios. Ask the child to self-reflect on how situations were handled and ways they could be handled in the future to end up with a more favorable result.

You can’t have these conversations in the heat of the moment, of course.

Sometimes, these are incidents of misbehavior that need the same discipline as if it were not an emotional outburst, but rather some other inappropriate behavior. Discipline isn’t punishment; it’s guidance. Don’t be afraid to confront inappropriate behavior and call it for what it is.

Being overly emotional because you didn’t get your way is only okay for very young children. Everyone else, even adults(!), needs correction when that happens. The correction can involve debriefing as described above, but it’s far better for the parent to practice this at home than for parents to leave it to teachers who by necessity have to try to address it in front of other kids. Not ideal.

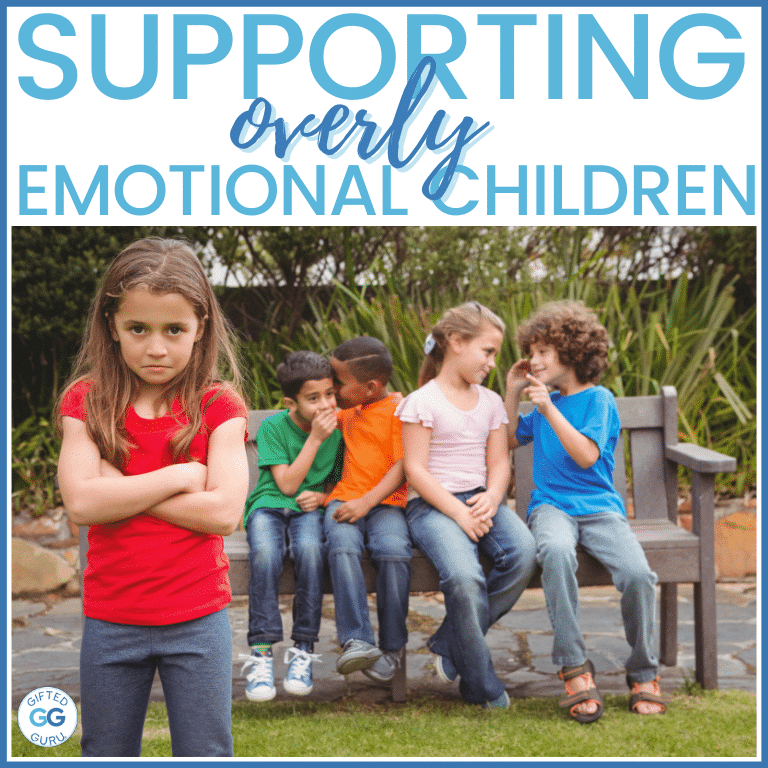

Question 2: How can I help him with other kids not wanting to play with him?

The first question to ask is: Is he a good choice to play with?

It’s hard to accept this because we want nothing more than for our children to be liked, but no one owes our children friendship. Everyone is owed courtesy and kindness, but we have to earn friendship.

Are there behaviors that are getting in the way of other kids wanting to play with him?

Are there things he could do to be a better friend to others?

Can the child reflect on things like:

- Am I kind?

- Do I share well?

- Do I take turns?

- Am I approachable?

- Do I use kind words and do I use them in a kind voice?

Playing together is a skill set. You need to take turns. You need to not always dominate the conversation or choice of what is being played. You can’t set your own rules for everything. You can’t be mean. You can’t show a lot of impatience.

I always wanted friends, but I wasn’t always a good choice to have for a friend. That was hard for me to admit, but once I did, it really helped me to realize that I could fix it.

Keep in mind that gifted kids often prefer older or younger playmates, so consider that if a child struggles to make friends with chronological-age peers, he/she may have better luck with older or younger people.

When I was with Mensa, I created this slidedeck from a presentation by Dan Peters on how to help your gifted children find friends that you may find helpful.

Sometimes when kids struggle to get others to play with them it’s because the kid is lacking skills, and sometimes it’s because it’s the wrong pool of peers.

Question 3: How can I get him to express himself when others say mean things to him?

I’m going to take a stab at this one, although I’m not sure if the question is “express himself appropriately” or “say anything at all.”

If a child is having mean things said to him/her, three questions need to be asked:

- Would everyone agree this is a mean thing to say, or am I being overly sensitive to it?

- Does the person truly feel this, or are they saying it for another reason? (For instance, are they saying something mean in response to something I did or said or because they’re mad/hurt about something else?)

- Is this a one-time thing, or is this something that’s happening often?

If everyone would agree it’s mean, the mean comments are not reasonable, and it’s happening in more than an isolated incident, it needs to be addressed.

How to address it?

If possible, the child should stick up for herself/himself with responses such as, “It’s not okay for you to say that to me.”

If that doesn’t stop it (Who are we kidding? It won’t stop it.), then it’s time to get assistance from an adult. Again, though, this isn’t after a single incident.

In isolated incidents, the best response is usually no response. Ignoring, walking away, single-words like “Wow”, or shrugging are usually all that’s required.

It’s reasonable for the adult to want to know details, so don’t be offended if it feels like disbelief. Questions such as, “Did you do anything that may have made her want to say that?” are reasonable.

While the adults are working to help problem solve the issue, consider these techniques:

1.Use visualization to help. Have the child practice imagining him/herself surrounded by an invisible Plexiglass shield that defends them against all verbal attack.

2. If the child is old enough to journal, I highly recommend it. This works well for adults, too.

3. Mindfulness meditation practices can help children stay calm in the moment. See the Emotional Health page for more information on this.

People will say mean things to us nearly all of our lives. Learning how to respond to it is a core life skill. It’s normal to have hurt feelings. It’s not okay to lash out physically or respond in kind. This takes practice. Lots of practice. In fact, I’m still practicing.

Book Recommendations:

I have a few books I recommend for students/parents/teachers surrounding these issues:

- The Kids’ Guide to Staying Awesome and In Control: Simple Stuff to Help Children Regulate their Emotions and Senses

- Don’t Let Your Emotions Run Your Life for Kids: A DBT-Based Skills Workbook to Help Children Manage Mood Swings, Control Angry Outbursts, and Get Along with Others

- How to Be a Superhero Called Self-Control!: Super Powers to Help Younger Children to Regulate their Emotions and Senses

- No-Drama Discipline Workbook: Exercises, Activities, and Practical Strategies to Calm The Chaos and Nurture Developing Minds

Wrapping Up:

Hurting others and being hurt is part of life, unfortunately. It’s not limited to children.

We can help our children navigate the danger-filled world of friendship and emotion by trying to be objective about what’s really going on and practicing actual skills.

We have to make sure we are not blaming others for our child’s growth opportunities, we have to find them a good pool of peers, and we have to practice skills (and model them ourselves!).

You May Also Like:

- Adaptive Giftedness & the Power of Connection

- Why School’s Not Fair to Gifted Kids

- When Gifted Kids Whine: The Therapist Answers

- You can find all of the Reader Q&A responses here.