Sending home classroom parent permission forms typically occurs at the beginning of the year. Unfortunately, no one teaches you how to do it. In college they don’t help teachers learn any of the really important stuff, like how to operate the copier or run a laminator, and I know they never told me how to write a good parent permission letter.

I have written specifically about the letter I use to onboard parents to the idea of differentiation. In this article, I’m sharing two things: how to write a good parent permission letter and the actual letter I use to get permission for use of some fidget toys I use in class.

How to Write a Good Parent Permission Letter

Writing a good parent permission letter will (hopefully) accomplish two things: 1) give parents the information they need and 2) help teachers and parents stay on the same page.

Here are some tips for how to make that happen.

1. Send the letter home after everyone else.

Parents are inundated with paperwork the first days of school. It’s crazy making for parents. It’s not great for teachers, either, because students sometimes change classes, so you can end up sending forms that you don’t need.

A pro tip is to wait just a little bit. Even just waiting until the second week of school makes it more likely that parents will actually read your letter.

If you send it home the first days of school, your letter will end up in the pile o’ paper that’s just part of the signfest parents endure. If you think they are reading and processing all of that while trying to get the family back on a school year schedule, then I’ve got a bridge to sell you.

2. Sound like a human.

Too often, permission forms sound like they were typed by robots. They’re institutional and formulaic. They sound exactly like every other form the parent is receiving.

Avoid this by writing as if you were having a conversation. Let your voice shine through. It’s very possible this is the first conversation you and the parent are having, even though it’s in letter form.

Don’t worry that if you are informal parents won’t take you seriously. A greater worry is that you will sound like an automaton.

3. Make it easy to read.

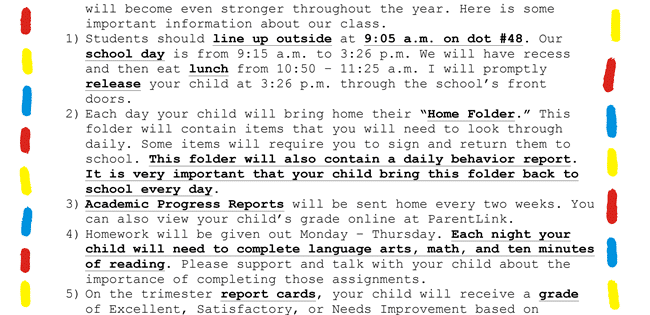

Readability is important. Too much text too close together, lots of bolding and underlining, and hard to read fonts make it less likely that your letter will be read, much less understood.

In this letter I randomly found on the internet, the text is difficult to read because of all of those issues.

4. There is no need to inundate them with information they don’t need yet.

In the example parent form above, you can see that the teacher is already telling the parent about trimester report cards. That is not information the parent needs the first week of school.

People are programmed to pay attention to what they need to know. We will subconsciously devalue information we don’t think we need. This can make parents disregard information they need because we gave them too much they didn’t.

5. Split it up.

Most teachers try to cram all of the information the parents need in a single form.

We end up with a form that’s too long or a form that’s ignored or a form that we’ve left needed information out of because we felt weird about sending such a long form.

Consider splitting it up over time. Send one page one week and another a different week.

I promise you this: a paper that comes home titled “The Essential Things You Need to Know This Week” is far more likely to be read than a form that is so long the title might just as well be “Everything You Ever May Possibly Need to Know But Maybe Not, So You Should Probably Just Ignore the Whole Thing.”

6. Use tech.

It’s silly to ignore the possibilties that exist with the technology available today.

You could record a series of short videos that explain the classroom to parents, upload them, and then include links to them (use a link shortener to make it easier for parents to navigate) in a single page letter.

You can also use Google forms to allow parents to respond. Currently, it’s probably best to make this optional, as some parents may not have internet access or be comfortable with it.

7. Translate.

If your students’ parents speak different languages, use Google Translate to translate it into the languages they speak. It isn’t perfect, but it’s better than no translation.

8. Share.

If you are not self-contained, meaning that you have students who are also students of other teachers, then you should avoid having parents fill out the same information (like contact information) over and over. Share.

9. Explain the rationale.

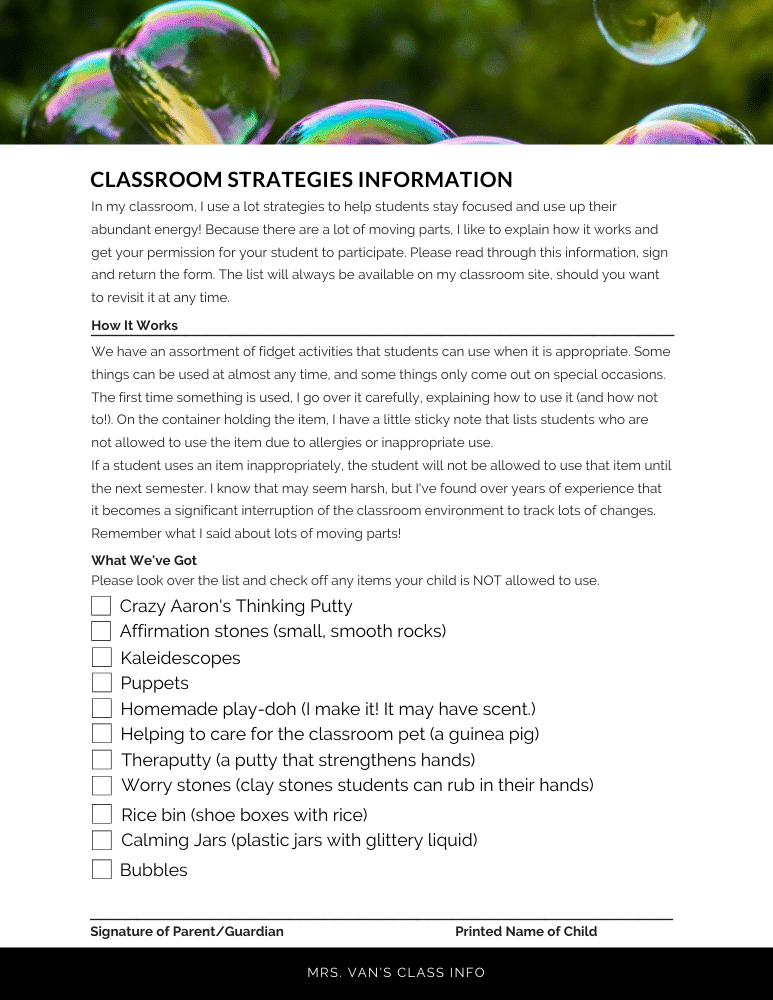

Rather than just writing rules and procedures, explain why the rule or policy or procedure exists. We can accept things better when we know their background. You can see an example of what I mean in the sample below.

Sample Parent Form

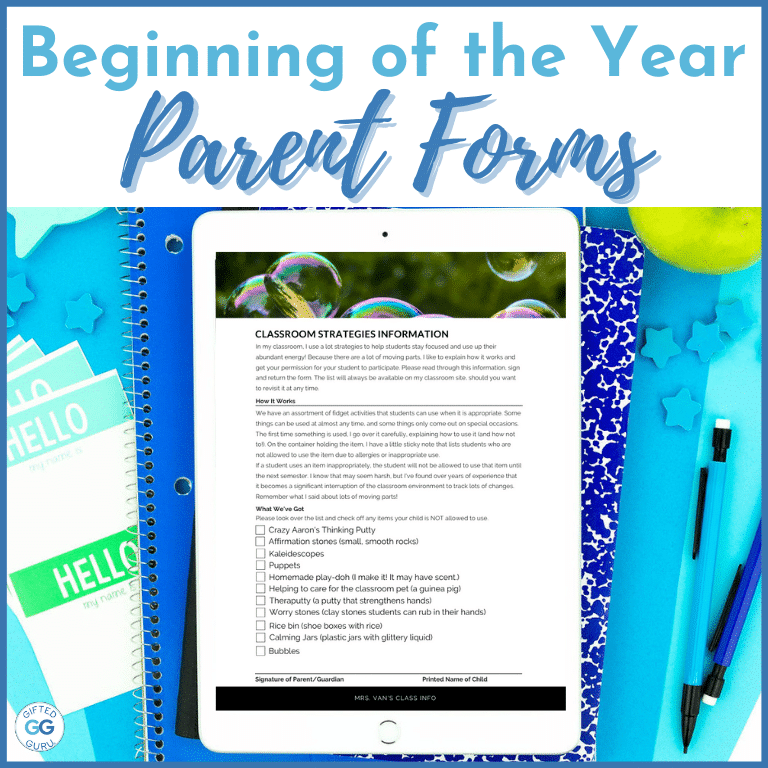

As I mentioned, I have a letter that explains differentiation that you can see. I have another letter I use to explain and get permission for use of fidget toys I use in class. If you’ve seen my Teaching Like Lucy session, you know what I mean.

Here’s the form I use for that.

While it wasn’t always available, now I use Canva to design parent forms because they have super great templates.

This is an example of a form that would be sent home by itself, meaning it’s not part of a bunch of other pages.

Wrapping Up Parent Forms:

Better communication with parents makes for a better experience for everyone. Getting a year started off right with parent forms that are well done is one way to make that happen.

Hopefully, these tips and ideas will help you create the forms that will benefit everyone in your classroom community.

You May Also Like:

- Making Choice Menus Better

- Quick Differentiation Technique: Scholar Extension Opportunities

- Group Work Self-Reflection Questions for Students

This article was written because of a specific question from a teacher. If you have issues or questions that you would like addressed, please reach out.

I send emails out once or twice a month that keep teachers in the loop. If you’re not signed up, you can join in the fun.