Have you ever wanted to be really good at what you do?

No, I mean really good. As in the best.

As in, do people think of you when they think of the highest quality of practice in your field?

I have.

And I have thought about it a lot more since I discovered Atul Gawande.

And no, that is not a beautiful atoll in the Pacific.

Atul Gawande is, on the surface, a doctor. But peel away the layers and you will find a renaissance man with lessons and ideas for all professions.

His books Complications, Better and The Checklist Manifesto have applications across virtually all domains – cognitive and affective.

At the end of his book Better, Gawande recommends five steps toward becoming what he calls a Positive Deviant.

These steps work for every role, including parent.

Perhaps especially parent.

Here are the five steps, along with ways I believe that educators can implement them.

1. Ask an unscripted question.

When you’re interacting with students, parents and administrators, ask something unexpected rather than just going through the normal/formal questions.

Use the opportunity to make a connection.

Gawande says, “You start to remember the people you see, instead of letting them blur together. And sometimes you discover the unexpected.”

See if every exchange can lead to bridge building.

Suggestions for educators:

Questions for kids:

- What do you think will be the best thing that will happen to you today?

- What did you have for breakfast?

- What day of the week is your favorite?

- What time do you get up?

- What’s the most unusual thing in your backpack?

- If your life were a book right now, what would the title be?

- If I could do one thing to make you smile, what would it be?

Questions for parents:

- What was the coolest thing your child ever did for you?

- What would you like me to know about your child that has nothing to do with school?

- What is your child’s biggest dream?

- How different do you think your child is at home than at school?

- Who, besides you, do you think your child loves most in the world?

- Who, besides you, loves your child intensely?

- What makes your child happy?

- Is your child happier today than he/she was last year?

Questions for other educators:

- Who was your most influential teacher?

- What is the craziest lesson you’ve ever taught?

- What is your dream classroom design?

- If money were no object, where would you spend summer vacation? Winter?

- If you could get every child in your class a book, what would it be?

- Would you rather more classes with fewer kids or fewer classes with more kids?

- What did you do last weekend that was unplanned?

- What would be the nicest thing someone could do for you today?

- What are your pain points today?

2. Don’t Complain.

There is nothing easier to do than to complain.

Conversation frequently devolves into complaining in virtually every arena – personal, professional, and even in social media.

Nearly everyone knows a Facebook Frowny Face.

Gawande’s second guideline is to avoid this at all costs.

Gawande says, “The natural pull of conversational gravity is towards the litany of woes all around us. But resist it.

It’s boring, it doesn’t solve anything, and it will get you down. You don’t have to be sunny about everything, just be prepared with something else to discuss: an idea you read about, an interesting problem you came across.”

Take Away: Prepare ideas or problems with which to change the subject.

Nothing is more irritating than a Pollyanna when you’re in a bad mood, but you can ease people out of the emotional doldrums by sharing your own turnabout strategies – a great book you read, a piece of music you liked, a terrific TED talk you watched, a Pinterest board you love, a blog you follow.

Rather than commiserating, try to open your mind to ways to ease the misery or divert attention away from it.

Misery may love company, but you don’t have to join the party.

Avoid anchor topics – references to people or situations that cast a pall on the brightest day.

You know who and what they are – don’t bring them up.

Think of them as Voldemorts – they who must not be named.

Be a counter revolutionary.

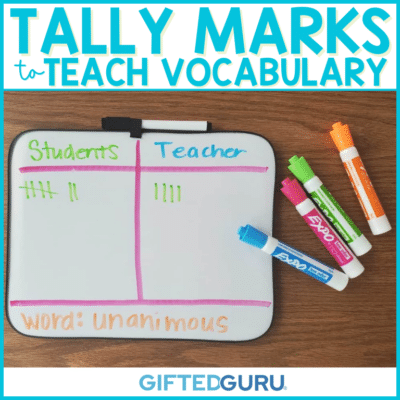

3. Count Something.

Little kids love to count, and then somehow we stop counting for fun (everything except grievances, that is).

You know, it’s kind of like running. Little kids run everywhere, and then at some point we start walking. And we stop counting everything.

Gawande suggests counting in order to keep learning.

He says, “One should be a scientist in this world. In the simplest terms, this means one should count something…

It doesn’t really matter what you count. You don’t need a research grant.

The only requirement is that what you count should be interesting to you… If you count something you find interesting, you will learn something interesting.”

Take Away: Track something that interests you that you are not required to track.

Be a scientist of your work or environment.

No one should know more about what you do than you do.

Statistics and data shared with you should never surprise you.

Ideas for things to count or track:

• How many days in a row can you greet everyone you see with a smile?

• Rate lessons you plan on a scale of 1 – 10 before and then after they are given. How well are you gauging your effectiveness? Ask trusted students to rate them and compare.

• How many times do you use a particular word in conversation?

• Count something to do with job performance.

If you’re an assistant principal, track the referrals that come in, looking for patterns.

If you’re a teacher, track homework turn-in rates by day of the week, class period or other criteria.

If you’re a parent, track patterns of your child’s successes and challenges with extended learning opportunities (homework by any other name…).

4. Write Something.

There is something about writing that forces reflection.

Gawande’s fourth suggestion is to write about what you are doing.

Writing about your professional practice creates a deliberateness that is lacking when we don’t reflect on what we’re doing.

Gawande says, “It makes no difference whether you write five paragraphs for a blog, a paper for a professional journal, or a poem for a reading group.

Just write. What you write need not achieve perfection.

It need only add some small observation about your world… by offering your reflections to an audience, even a small one, you make yourself part of a larger world…

The published word is a declaration of membership in that community and also of a willingness to contribute something meaningful to it. So choose your audience.

Write something.”

Take Away: Find your medium (blog, journal, Facebook, Twitter, wiki, etc.) and write away.

Observe your world with words and then cast that bread upon the waters.

Share your reflections.

Ah! For once I’ve taken my own advice.

Find other teachers’ or administrators’ blogs or websites for examples.

Read other teachers’ books –

- Educating Esme

- The Courage to Teach

- Teaching outside the Box

- Crossing the Water

- Inside Mrs. B.’s Classroom and more.

5. Change

The pointy thing that sticks out from the front of ships is called the bow sprit.

Its purpose is to allow the front sails (called jibs) to be able to be anchored farther forward than they otherwise would.

In older ships, they were painted white unless the ship had been to the Arctic or Antarctic, in which case they were blue.

When we embrace change with open minds and bring our professional skill and creativity to trying to implement it, we become the blue nosed bow sprits of the campus – leaders rather than followers.

Decide now to be a blue bow sprit.

Embracing change makes you proactive rather than reactive, and it is a position of strength.

Gawande encourages, “Look for the opportunity to change.

I am not saying you should embrace every new trend that comes along.

But be willing to recognize the inadequacies in what you do and seek out solutions.

As successful as medicine is, it remains replete with uncertainties and failure.

This is what makes human, at times painful, and also worthwhile…

So find something new to try, something to change.”

Take away: Focus on becoming an early adopter, even to forced change.

This is just a remix of the old adage, “If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em.”

Bring in your own change, so that change is not merely reactionary on your part.

Think of one thing you’d like to change this year, even something small.

Write out the steps of it, gather the supplies, and implement the change.

Motivated? Can’t get enough? Join Gawande Boot Camp and get a coach.

Read about how Gawande himself became a better surgeon by enlisting the help of a coach here.

Avoid resenting change.

Embrace it by using other positive deviancy steps (write about it, count it, don’t complain about it).

Ask how you can you be a change agent rather than a change resister.

The bottom line?

Five simple steps can take you personally or professionally from adequate to outstanding.

The time will pass whether you are improving or not.

What are you waiting for?

Deviate! I’d love to hear your unscripted questions.

Go ahead: ask me!