You should memorize poetry, and I’m going to share ten reasons why. This is general advice that is good for everyone in manner of “wear sunscreen.”

I love poetry. I’m not just saying this because it sounds good at cocktail parties to say you love poetry. I truly love the rhythm and the way that in very few words, a poet can evoke strong feeling in me.

Kids love poetry, too. It’s innate – we love rhyme as children and are charmed by it. Of course, on the playground, it’s sing-songy and often violent (Not last night but the night be-fore, twenty-four robbers came knocking at my door…), but it teaches meter to kids who won’t hear it again until 9th grade as “two households, both alike in dignity” come on the stage when they encounter Romeo and Juliet for the first time.

As a teacher, I decided to start assigning poetry memorization when I read The Best Loved Poems of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, and decided that everyone needed to know at least some of Tennyson’s “Ulysses” if they were to pretend to know anything about Homer’s “Odyssey“, which I was teaching at the time. To hear teenage boys stand and recite,

“To follow knowledge like a sinking star, beyond the utmost bound of human thought…to strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield”

….well, there was beauty and majesty in it. Trust me on this one.

Memorizing poetry is a great tool for parents and teachers of the gifted. Here are your ten reasons why (some are tongue-in-cheek, so be forewarned) you should memorize poetry:

1) It is a brain challenge. Got a kid with a strong memory? I’ve got some long poems for you. Interested in history? Learn a poem based on a historical event or some of the poetry of that period.

For anyone seeking a way to challenge a gifted child in way that is free (!) and virtually unlimited, you’ve found it. Even copying poems down (or lines of poems) and illustrating them is a wonderful activity for younger children.

2) We need good stuff in our minds. POWs report extensive interaction with what they had in their minds before they were taken prisoner as a mind-saving activity. Now, most of our children will not become POWs, but they most definitely will be stuck somewhere, sometime, where all they have are the things they carried in their minds. Think waiting lines. Doctor’s offices. Classrooms (some of them – admit it).

I read once that Senator Byrd (an amazing autodidact) knew so much poetry that he could recite it all the way from his home in West Virginia to D.C. and back. That’s twelve hours of poetry, folks.

3) It improves English styntax complexity. Susan Wise Bauer, author of The Well-Educated Mind: A Guide to the Classical Education You Never Had, writes that memorization “builds into children’s minds an ability to use complex English syntax.”

She likens a child’s language to a store, and says that memorization fills “the language store with a whole new set of patterns.” As the complexity of what our children read in school declines, what they encounter outside of it becomes ever more important.

That same Senator Byrd once said that he loved his home state so much that when he died and they opened him up, they’d see “West Virginia” carved on his heart. That’s poetry. It’s not complex, but his poetic store enabled him to think in ways that were unusually evocative.

4) It makes other things more enjoyable. I remember standing in front of a beautiful tapestry and realizing that the poem “Aedh Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven” by Yeats was augmenting my ability to appreciate the art. I could see the words of the poem woven into the fabric, “enwrought with golden and silver light.” I could imagine the artist laying the work at my feet, and it reminded me to tread softly because I was treading on dreams.

Watch Sir Ken Robinson read that poem here (it’s at 15:15).

Children can learn through poetry a deeper appreciation for the beauty around them as they internalize the beauty of the poetic lines and apply it to what they see.

There’s a reason that the boys in Dead Poets Society got hooked on poetry and resurrected the club to celebrate it: it made their school experience overall more enjoyable (well, at least until the one boy committed suicide, but that was in no way the poetry’s fault, you must agree).

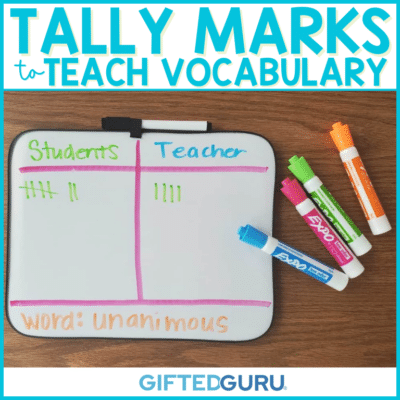

5) It improves vocabulary. Memorizing words out of context or will their definition in isolation makes it unlikely that the word will become a part of the person’s bank of used words.

Long lists of “SAT words” do little good other than as preparation for a single test unless one learns to incorporate the words into the way language truly operates.

Poetry helps fix the context of complex and unusual words in our minds, making it more likely that they will be used later – in essays, in job interviews, or when one is simply trying to express deep feeling, emotion, or thought.

6) It is beautiful. Byron’s “She Walks in Beauty Like the Night.” Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s “How Do I Love Thee?” Louis MacNeice’s “September has Come” excerpt from “Autumn Journal.” The words almost have color, they are so lovely. All that’s best of dark and bright meet in the aspect of poetry, to twist Byron.

7) It builds a framework. I memorized Wordsworth’s “Ode to Intimations of Immortality” after seeing the Natalie Wood/Warren Beatty movie Splendor in the Grass. The poem then became a framework for the memory of how I came to love the work of Natalie Wood.

When a memory has a poem attached to it, it strengthens both the memory and the remembrance of the poem. My son Greg used to call it “rememborizing” when he was three or four. You both remember and have committed to memory.

You now have a framework to which to attach new memories, new knowledge, new poems, and new information. You feel smarter, too, because you catch all the allusions in pop culture to poetry (you’d be surprised – if you don’t see it, you need to learn more poetry!).

8) It’s a great party trick. If you’re ever stuck for a spur of the moment talent, you’re in luck if you’ve got a poem in your mind you can whip out and recite from memory. It’s easy, it needs no props, and you will not be doing the same tired trick as everyone else. Unless they read this article.

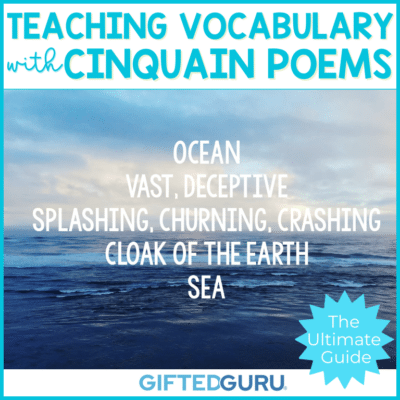

9) It’s a bridge among disciplines. The multitude of poetic forms embrace patterns that even die-hard math fiends will find resonant. The more restrictive and complicated the pattern, the more likely is that the mini-me Euclid will enjoy it.

There are poems about seasons (“April is the Cruelest Month” from Eliot’s “Wasteland”), about science (Whitman’s “When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer“), about art (Melville’s “Art“) and on and on. Teachers of languages other than English can have students memorize poems in the target language.

10) It keeps us connected. In poetry, I know I am not alone with my feelings. Others have grieved as I have grieved (see Edna St. Vincent Milay’s haunting “Sonnet II” or John Donne’s unwavering “Death Be Not Proud“), have loved as I have loved (see Shakespeare’s ever-hopeful “Sonnet 116“), or brooded in ennui-filled sentimentality as I have (see Tennyson’s “Ulysses“).

Poetry enables us to connect with each other as well. My mother and I share a love of Cavafy’s “Ithaka” – I wrote it in calligraphy for a gift when she graduated from college, and we quote lines of it to each other with frightening regularity. Poetry can help us say what we could not have otherwise said, to each other and to ourselves.

If I’ve convinced you, here are some resources:

Mensaforkids – Find the “Living Poetically” program I wrote, complete with twelve pieces to get you started, along with helpful tips and practice exercises. This is one-stop shopping primer for how, why, and what to memorize. Warning: not all of the poems there are suitable for wee ones.

ESSENTIAL PLEASURES: A New Anthology of Poems to Read Aloud – This valuable book embraces the utter necessity of reciting poetry aloud. A must-have for the poet lover (or novice).

Poetry 180 – Former Poet Laureate Billy Collins and the Library of Congress (let’s just pause for a moment to reflect upon the wonder that is the LOC) bring you this program, a poem a day for each of the 180 days of the typical school year. The poems are particularly appropriate for students, so this is a great resource for teachers.

Poetry Foundation – Check out the Poetry Foundation’s children’s page. It has resources as well as poems, specifically recommendations on specific books of poems for children.

Giggle Poetry – There once was a website that said/ funny poems are all in your head/ if you practice just right/ and your mind takes flight/ you can put your dull thoughts to bed. You, too, will be writing amazing limericks (okay, acceptable limericks) after you visit this website. It’s particularly good if you have a very young or a reluctant poet. Or, like me (clearly), a budding limericist.

Poets.org – This website has a fairly comprehensive list of ways to teach poetry – meaning how to include it in an organic way. There are tons of resources here to keep you poetically busy for a long time.

Even very young children can memorize poetry, and, in fact, many of them enjoy it. See the video below to watch a 3-year-old recite one of my faves – Billy Collins‘s “Litany” – a hysterically ironic frenemy poem from one lover to another. If you want to teach a child metaphor, this is the poem for you. I must warn you, however, that you will be forever saying, “There is simply no way you are the pine-scented air” on random occasions.

You may believe that inviting young children to memorize program is simply drill-and-kill, but friend, I beg to differ.

You may believe that you are too old or too uninterested in culture to memorize poetry, but friend, I beg to differ.

You many not be the pine-scented air, but you can fill the air around you with the beauty of language masterfully crafted.