Why Don’t Students Like School?

Dan Willingham’s Why Don’t Students Like School? is one of the best books I have ever read for teachers. Thank you for letting me explain why this is a book you must own for yourself.

Confession: It took me two years to read this book.

It was not because I didn’t like it. In fact, the opposite is true. The reason is this:

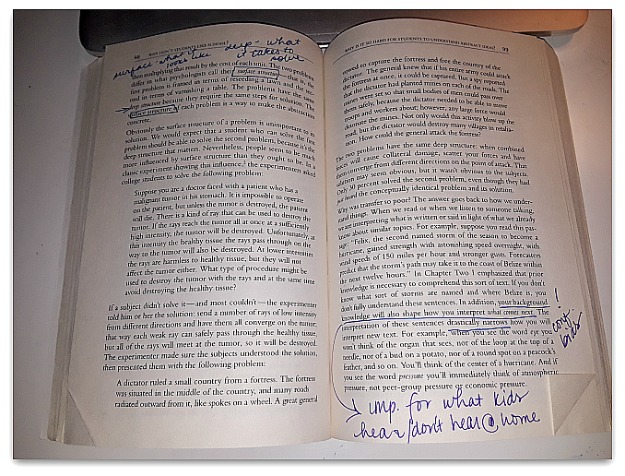

I had to have a conversation with nearly every page.

[And I don’t want to hear any book purists criticize me for folding pages. I learned at the feet of a master, so blame Ryan Holiday.]

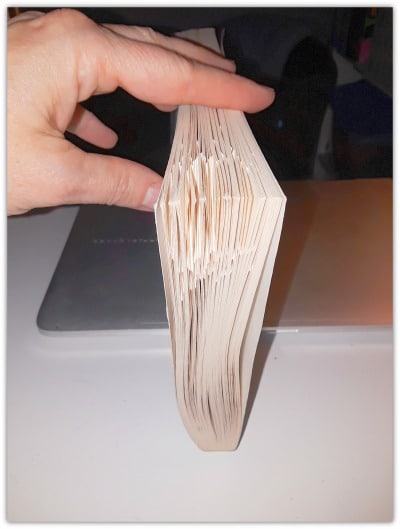

I left no page untouched. They all look like this (at least).

Along the way, I developed a neurocrush on author Dan Willingham, who has no idea I exist. Sigh. It’s high school all over again.

Because I wanted to continue my book date with Dan, I would put the book down, allowing myself only a few pages at a time. I stretched it out like rationing my fave Halloween candy.

What I liked:

Everything. Simply Everything.

This is one of only two books teachers need to be amazing. (The other is Doug Lemov’s Teach Like a Champion, which I briefly mention in this article). I know, I know. Only two? Yes, if they’re these two.

Let’s dive in a little deeper. What exactly is so amazing about this book, you ask?

What you’ll learn in this book:

Here are my take-aways from just the first two chapters (page numbers are in parentheses):

-

“The brain is not designed for thinking. It’s designed to save you from having to think”…because of this, “unless the cognitive conditions are right, we will avoid thinking.” (3).

-

“We normally think of memory as storing personal events…our memory also stores strategies to guide what we should do” (7).

-

We derive cognitive pleasure from the solving of problems, not being frustrated by them or having answers given to us (10).

-

Teachers should make sure there is a level of cognitive work that “poses a moderate challenge” (19) – avoid long string of teacher explanations” (19).

- Don’t overload the working memory.

- Respect the limits of what kids already know and create intriguing questions the knowledge they have will answer.

- Shift often.

- Keep a diary – recording success – (be your own scientist).

- “It is often true (though less often appreciated) that trying to teach students skills such as analysis or synthesis in the absence of factual knowledge is impossible” (25).

- “Factual knowledge must precede skill” (25).

- “Chunking works only when you have applicable factual knowledge in long-term memory” (34).

-

“Good readers” has a strong connection with “good knowers” – you understand better what you know better.

-

Background knowledge is important because it provides vocabulary, allows to bridge writing gaps, allows chunking, and guides interpretation of ambiguity.

-

Explanation for 4 th grade slump (37) as shift from decoding to comprehension, which is much more dependent upon background knowledge.

-

Even if you comprehend equally, if you have background knowledge, you’ll remember more (42).

The part where he had my back:

I particularly liked his explanation of how teaching experience is not the same as teaching expertise.

As someone who has led professional development for tens of thousands of teachers, I would love to have this emblazoned on the sign-in sheets. So many people come thinking that because they’ve taught for x number of years, they don’t need any more training.

I have had many people actually say this to me.

And the rest of the book is like that. It’s imminently readable and practical.

Why Don’t Kids Like School? is so, so worth reading if you are an educator.

The part where I got nervous:

In the chapter on how to help slow learners (Chapter 8), I got nervous because this is where the super aggressive anti-gifted kid people usually show their true colors, forcing me to drop them like the proverbial hot potato.

I literally read the chapter with my shoulders scrunched up, waiting for the “don’t label kids as gifted” ax to fall. I’m feeling especially vulnerable to this because of some anti-gifted rhetoric recently.

Luckily, I agreed in principle with Dan. I do think it takes more explanation, though, so let me provide it.

My mini-lecture in support of gifted education

Dan shares some of the anti-praise research, and I’m a big fan. He says, “How can it be a bad idea to tell a student she’s smart? by praising a child’s intelligence, we let her know that she solved the problems correctly because she is smart, not because she worked hard. It is then a short step for the student to infer that getting problems wrong is a sign of being dumb” (182).

Note: My grandparents are deaf, and I object to the use of the word “dumb” in this context, but I understand and accept that others outside of deaf culture may not mind.

Okay, so what needs clarification in my opinion is that this idea that praising ability instead of effort is damaging is being used to argue that you shouldn’t label kids as gifted. I’ve written about this before, and it needs to be said again and again, especially when big names like Jo Boaler at Stanford are singing this song.

The distinction is that identification of children for gifted services is not praise.

Dan says that intelligence is seen as desirable, and I agree that is where the problem comes in. Because it is seen as desirable, people possessed of it are often envied. Envy leads to hate and resentment.

It does not actually matter whether the child in school is smart because of nature, nurture, a complex interdependence of the two, or a good sale on neurons at Amazon.

The gifted child in school needs assistance in a very similar way to that the child who is a slower learner does. They are atypical, and they need help in navigating an environment created for the typical.

Do we require proof of how a child obtained a learning disability before we meet their needs? Do we worry that the label “dyslexia” will be harmful, so we just force them to go for it with no help? We used to, and we harmed hundreds of thousands of kids.

We cannot let this not be true for gifted students simply because some people have used the label incorrectly.

It is critically important that students understand why they’re smart, what being smart really means. It means (probably) that their native intellect combined with their environment and experiences, leading to effective thinking practices.

They must apply those effective thinking practices through concerted, diligent practice and effort in order to be successful. If they do not, they will be far less well off than those of typical intelligence who apply themselves.

It doesn’t mean things will be easy, that they don’t have to work, and that if they struggle, they need to take the WISC again.

Identification is not praise. It is acknowledgement of difference.

Would you agree, Dan? If not, it may cure my crush permanently.

Wrapping Up

Go get Why Don’t Kids Like School? You need to own it. You need to read it. You need to do these in that order because of all of the marginalia you’ll write, even if you’re a purist.

Worth Reading Rating: A rousing and heartfelt 5

You can learn more about my Worth Reading Rating System here.

(Note: this post contains affiliate links, which means I receive a few pennies if you make a purchase using the link, but it doesn’t cost you anything.)