Gifted students should not be used as tutors for other students as standard practice.

This should not be a controversial statement, and yet somehow it is.

Gifted children should not be used as short little mini-teachers for other students for a number of reasons, not the least of which is they’re not good at it.

Even if someone is unconcerned with what is fair or best for the gifted child him- or herself, the gifted child is not the ideal tutor.

If we do concern ourselves with what is fair or best for gifted children, we must accept that the gifted child deserves more than that out of their education.

While I’m the first to admit that teachers have more responsibility on them than is reasonable, I would also argue that the answer to that is not to outsource the burden to the gifted child.

Some will argue that they know a gifted child who loves being a tutor and is good at it.

That’s great.

Unfortunately, it’s not the norm. And even if it were true of all gifted kids, I still would argue it’s not the best use of their instructional time as a pattern.

Let’s unpack the arguments regarding used gifted students as “helpers.”

Traits of an effective tutor

Let’s look at what it takes to be an effective tutor.

- The ideal tutor has a lot of patience.

- The ideal tutor has the inclination and ability to explain the same concept over and over without appearing or feeling frustrated or impatient.

- A good tutor has the ability to see the concept in the same way that the person does who is trying to learn it.

- Strong tutors don’t take over and do the work for the person.

Traits of gifted learners

Let’s look at gifted learners through the lens of the traits of an effective tutor.

Gifted learners are not known for patience. (You can make the argument that they’re partly not known for it precisely because they are inappropriately put in the position of tutor.)

Gifted students may not wish to try to explain something to someone else who doesn’t get it yet. They may not find any satisfaction at all in trying to figure out multiple ways to explain something and may not even try.

Gifted children do not just think more efficiently; they think differently.

Their thought processes are not the same as their chronological age peers.

Just because a gifted child has mastered a concept does not mean that child is then in a position to explain that concept with any degree of success either academically or socially and emotionally to their peers.

This last issue is the most compelling in my experience.

Gifted kids don’t necessarily explain things well. They don’t always go from Step A to Step B to Step C to the end.

They sometimes go from Step A to Step H, completely and blissfully unaware that most people threw six more steps in there.

They often tesseract from step A to the end, and if they’re explaining the process to somebody else, that’s going be problematic (note A Wrinkle in Time reference).

It’s exactly the opposite of what a student who requires extra assistance needs.

The temptation to take over and just do the work is strong. It’s as powerful as the Force.

As the great philosopher Yoda says, “Take over, they do. Get the work done, they must.”

Unfortunately, one of the problems is that teachers often use tutoring as the fast finisher solution.

If a gifted child finishes their work before everyone else, often the default mode is to have them then help others.

Whenever I see this as a recommendation, I throw up a little bit.

As I’ve already explained, they’re just not that good at it as a general rule.

You don’t really get an effective solution.

Instead, what you have is a student who was supposed to be learning the concept with help from a tutor, but that student didn’t learn that concept because the tutor was not in a great position to give tutoring.

You also have a student who, when they had mastered a concept, was not not allowed to move forward in depth or breath with the concept, but rather expected to go back and explain that concept to a peer.

It’s unfair to both students.

What about the benefit of review?

You can make the argument that by tutoring others, gifted students get to review their own learning.

I am the first to admit that review is crucial in truly understanding content.

I’m on board with the neuroscience studies that demonstrate that the more we go over content, the better we learn, the more entrenched it becomes, and the stronger the neural pathways develop.

This is all true.

The problem is that explaining a concept that you’ve learned to your peer in your classroom who does not understand that concept is not a great review activity.

A strong review activity requires that the person who’s providing the review has the ability to give quality feedback.

Virtually the only feedback that the person who the gifted kid is supposed to tutor can give is, “Yes, I get it” or “I still don’t get it.”

Of course, they don’t usually admit they still don’t get it because they don’t want to look stupid in front of a peer.

Struggling students are not really in the position to give the gifted kid any feedback on how well the gifted students has mastered the content. And that’s fine. They shouldn’t be expected to be able to do that.

The tutored student cannot identify the subtle nuances that need to be refined, explored, or corrected.

Gifted students need review, too, and there are other students who need additional time in order to master concept.

I think we can agree about these things.

What we may not agree on is what the answer is.

I would argue vehemently that the answer is not to have the gifted child be the tutor.

What about the benefits of explaining something to someone?

I agree that it is true that when you explain something to someone, you often learn it better than when you just think it to yourself.

You know how I know? I can describe the difference between personification and anthropomorphizing because I’ve had to explain it to students six billion times (right after I explain hyperbole).

Many of us as teachers have only truly, madly, deeply learned things when we’ve explained it to our students.

However, there are ways to do that more effectively with gifted kids.

It would be more effective to have two kids who have already mastered the content explain the content to each other.

That way, they are able to have that experience of explaining it and they are more likely to be able to make any corrections or share additional insights.

It becomes a mutually beneficial experience, rather than simply something for the gifted kid to do or a way to help the kid who needs tutoring without having it be the responsibility of the teacher.

We are essentially outsourcing the teacher’s responsibility as punishment to the gifted child for early mastery of a concept.

We are justifying it with an “any benefit” fallacy – that something is good if there is any benefit to it whatsoever. (Technically in logic this is a fallacy of composition for you purists.)

While you could argue that review is a good general practice and that a gifted child may benefit from explaining something they’ve learned to another students, I still argue that the practice is patently unfair.

Having a gifted student be a tutor doesn’t benefit either child enough to justify the inherent flaws in the dynamic.

In the end, I don’t feel that it even really benefits the teacher.

What about the benefit of helping others?

Helping others is terrific.

I would argue it loses its luster when forced.

Have you ever been in the position of having someone be forced to help you? It doesn’t feel great to either person.

When we assign gifted students to help others, we rob the gifted child of the opportunity to offer help and develop emotional intelligence.

It’s the same dynamic as forcing an apology. Sure, they said “sorry,” but their heart’s not in it.

If we allow gifted students to offer help rather than force them to, they get the “feels” of offering help and we make it more likely that they’ll offer more appropriate help.

What about the More Knowledgeable Other?

I’m a fan of the Zone of Proximal Development model, yet there is one part of it that is frequently wielded as a weapon against gifted kids.

I’m speaking of the More Knowledgeable Other stage of development, where you are guided from what you don’t know to what you know by someone who knows more than you.

If you read about this vis-à-vis education, you will assuredly find someone explaining that the MKO can/should be another student.

Here’s the problem with that: it’s assuming a fact not in evidence.

It’s assuming that a gifted child is an MKO simply because they may have the content knowledge.

Being an MKO is about far more than content knowledge – it’s about knowing how to convey that knowledge in a way the learner can grasp.

We’ve all known teachers who were content masters but had no other skills. They don’t make great teachers. The same is true of kids.

No part of the theory says that this should come at the expense of the MKO, which is what I would argue happens when we make gifted kids the tutors instead of the learners.

Damage to peer relationship

A common dynamic is that that the gifted child is expected to tutor, and so they do.

They don’t do a good job at it. They get frustrated. They run out of patience. They may even just grab the paper and say, “Here, let me do it” or give the answer without making sure the student they’re tutoring has grasped the concept.

The student who is supposed to be being helped by the gifted child is also frustrated, and perhaps shamed.

The relationship breaks down, and it is almost always blamed on the gifted child who is characterized as arrogant and stuck up, and an elitist intellectual snob.

The forced tutor feels resentment towards the person needing help (who may not have wanted it, actually), and the relationship is now circling the drain.

We have to understand that as soon as you put one person in the position of tutoring another person, you changed that relationship.

It’s no longer a peer relationship.

It is now putting one student in a position of intellectual authority over another.

This is, yet again, a patently unfair position to place the gifted student.

Now, we’ve disrupted the emotional ecosystem in the class.

There is a difference between two students in a classroom helping each other every now and then.

I’m not talking about student who leans over to a peer and asks, “Wait, how did you get your Bunsen burner to do that?” or “How did you get to that screen?”

Students can and should help each other on an ad hoc, informal, as-requested basis.

The difference here is that the person being asked is just as likely to be the ask-er next time, and they both know it.

That’s not what I’m talking about.

I’m talking about when the teacher assigns the gifted student to help someone else.

That’s a different dynamic, and it is an unhelpful dynamic to both students.

To the extent that it creates an unhealthy social environment in the classroom, it also harms the teacher.

The two things gifted students deserve

Gifted students deserve two things, and neither of these things is available in a tutoring scenario.

First, they deserve differentiated instruction from well-trained teacher. I’ll talk more about that a little later.

Secondly, they deserve to learn something in their educational experience.

Over a decade ago, Del Siegle, a genuinely great guy, wrote the the NAGC Gifted Children’s Bill of Rights.

Number two? “You have the right to learn something new every day.”

It will not shock you that one of the rights is not tutoring opportunities.

Gifted kids did not sign up for going to school simply to help other kids.

Should we all help each other? Of course.

But let’s be honest: that’s not what this is.

This is one group of students frequently being asked to set their own learning aside to perform a task at which they are at a distinct disadvantage.

This isn’t kindness: it’s exploitation.

These aren’t one-off experiences. For many kids, this is the default instructional model.

I’ve even seen it on posters in classrooms: “If you finish, go help someone else.”

This is not appropriate. It’s pedagogically inferior to, “If you finish, you get to keep learning and I’ll try to balance the time better next lesson.”

It’s a cop out.

Distance learning implications

Some parents and educators have noted that distance learning can be better for gifted kids than in-person instruction.

They can go at their own pace, and they don’t have to wait for people during every lesson.

I personally believe that in-person learning offers experiences that virtual learning cannot match and will never match.

However, one of the things it does is that benefits kids is that it takes the responsibility for tutoring off gifted kids.

If they finish, they’re just done.

This creates its own problem because their parents are confused about how there are only two hours of learning in an entire school day.

What this means is that if students are in a distance learning environment, it is essential that educators figure out how to differentiate for the gifted learner, and it is essential that teachers figure out how to give additional support to the students who need it.

Distance learning puts the responsibility for student support on the teacher.

If we can do it virtually, we can make it happen in face-to-face classrooms, too.

Having gifted kids tutor is a symptom of a bigger problem

One question we need to ask is, why do gifted kids have all this time to tutor?

It’s because they finish early due to a lack of quality differentiation.

How do we fix the issue that gifted students often finish early effectively?

I’ve written articles about ideas for fast finishers both for students and for teachers.

However, these ideas are typically necessary when the differentiation of the content was not satisfactory.

If differentiation is built into the lesson, gifted students will finish early less often.

Of course it will still happen, especially on shorter assignments, but it will be far less common.

For years, I’ve been advocating that lesson planning should begin with the most-able learners in mind.

This isn’t because they’re more important.

It’s because it saves time and ensures they’ll be considered.

I’ve written an entire article on how to plan your lessons with the most able learner in mind.

If you are unsure of how to plan a differentiated experience from the beginning, I’ve got an article on how to create a differentiated lesson plan, step-by-step.

There’s even a video of me actually planning a lesson in real time.

Now, that’s excitement.

What to do with students who need extra help or support?

We have students who need additional support.

Sometimes they’re the gifted kids. #truth

Here’s the problem: there’s a discrepancy between the amount of time that it takes to support learners in needs of extra support and the amount of time that teachers have.

There are a couple of answers that can work.

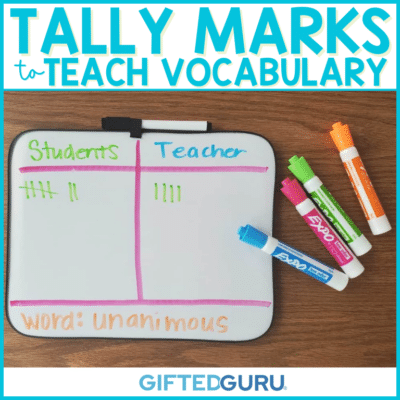

One is that you can have students who have finished the work record tutorial videos or screencasts where they make suggestions or share ideas about how they solved a problem, completed a lab, or figured out a concept.

Other students can watch these videos.

Why is this better?

- If the video isn’t helpful, the student can stop watching.

- The student who made the video doesn’t know who is watching, so they’re not placed in that awkward position of always being the tutor.

- If I’m watching the video in order to learn more, I don’t feel badly because I know that the person who made it doesn’t even know whether I was watching.

- Gifted kids can watch each other’s videos and have real peer-to-peer benefit.

Another idea is that the teacher can record tutorial videos or screencasts when they’re preparing the lesson.

Yes, it adds time to the lesson planning, yet I would argue that it saves time in the long run. You only need to do it the first time you teach it, and you can use the videos over and over.

You can crowdsource with colleagues and create a tutorial library, or you can find appropriate videos on YouTube.

If you’re teaching virtually you can build this right in as a link in the assignment.

If’ you’re in a face-to-face classroom, you can put a QR code on the assignment that says, “Need some more explanation of this? Scan me!”

Campus and district policy and practice

I’m not parking this bus on teachers alone.

All too often the only plan a campus or district has for gifted learners is to have them help others.

That’s unacceptable and ridiculous.

It’s as unsupportable as saying that a student who is struggling should just skip those questions.

Luckily, that’s illegal.

We must have programs that are intended and designed to serve gifted students for who they are and the strengths they possess.

Anything else is unacceptable. Anything else is an indefensible abdication of the district’s responsibility to make sure that school is a learning experience for all children.

If you cannot do that, then I would question what you could possibly be doing instead.

Wrapping Up:

Gifted children should not be used as “helpers” or tutors for other students in lieu of quality educational opportunities.

While they can and should be encouraged to be kind and helpful, this should be mutual. They should benefit from help as well as offering it.

Ironically, the same teacher who expects the gifted kid to tutor is often the same teacher who thinks that if a student needs help with something, they’re not really gifted.

Gifted children can gain every benefit of review or teaching in more appropriate ways.

The danger is not a single experience, but rather a pattern of a lack of differentiated instruction.

Other solutions exist for fast finishers and students in need of support.

We should not punish children for being gifted by making them perform a task for which they are ill-suited and which does not sufficiently benefit them to justify making it their common learning experience.

We can and should do better, both for the gifted students and the students who need additional help.

You may also like:

- Being Gifted Doesn’t Mean You Don’t Need to Be Taught

- Why School’s Not Fair to Gifted Kids

- Trying to Make School Better for Gifted Kids

If you would like to join the thousands of other people just like yourself who care about gifted kids, please join in by getting on the email list here.