Haiku in the Classroom

How can you use haiku do in your classroom? A quick list includes:

- As practice on a standard

- As a way to write across the curriculum

- For creative expression

- As part of a larger unit on poetry

- On summative assessments as a tool for gauging understanding and application

- And more! (keep reading!)

It’s no secret that I love poetry. I love teaching it, reading it, and even writing it.

In second grade, my classmates accused me of cheating when I wrote my first haiku. Their (false) accusation stung, but I’ve never forgotten the lesson that even young children can write poetry.

If you’ve ever considered using haiku in your classroom, I hope you find these ideas and resources helpful.

What is Haiku?

The Haiku form of poetry comes from Japan, although it is written slightly differently in

English. Haiku poems are short, so the topics are usually one simple thing (an animal,

something found in nature, or a season).

There are three common elements in traditional haiku poetry.

- There are 17 syllables in the poem – five in the first line, seven in the second, and five

in the third line. These lines rarely rhyme. In English haiku poetry, the number of

syllables is not as rigid, with some poems have ten or fourteen syllables instead of

seventeen. - A “season” word, called a kigo, is often used in traditional haiku. It doesn’t mean the

name of a season is used. Most often it is a symbol of a season (pumpkin, harvest

moon, snow, green, etc.). - A “cutting” word, called a kire or kireji, is often used to separate the beginning of the

poem (typically the first two lines) from the end (usually the last line) in traditional

forms of haiku. Instead of word, a poet may also use a punctuation mark, such as a

dash (—), a colon ( : ), or a semi-colon ( ; ).

Benefits of Using Haiku in the Classroom

Teaching haiku poetry to children offers so much in exchange for the seventeen syllables. Here are some of educational and developmental advantages:

- Simplicity and Structure: Haiku is a concise form of poetry with a specific structure (3 lines with a 5-7-5 syllable pattern). This simplicity helps students grasp the fundamentals of poetry and provides a structured framework for their creative expression.

- Cultivation of Observation Skills: Haiku often focuses on nature and the changing seasons. Teaching students to observe and appreciate the world around them encourages mindfulness and a deeper connection to their environment.

- Encourages Creativity: Despite its brevity, haiku challenges students to convey a vivid image or emotion within a limited space. This encourages creativity and imagination as they learn to express complex thoughts with few words. Constraint = deeper creativity.

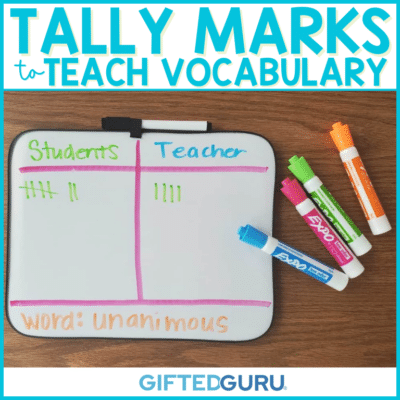

- Language Skills: Writing haiku can enhance language skills by promoting vocabulary development, syllable counting, and an understanding of poetic devices. It also encourages precision in word choice.

- Cultural Awareness: Haiku originates from Japanese culture, and teaching it provides an opportunity to introduce students to different cultures and traditions. This can foster cultural awareness, curiosity, and respect for diversity.

- Emotional Expression: Haiku often captures fleeting moments and emotions. Teaching students to express their feelings in a condensed form can help them develop emotional intelligence and an understanding of the subtleties of language. I am a huge fan of integrating social/emotional learning and content.

- Reading Comprehension: Analyzing haiku poems can improve reading comprehension skills. Since haiku often conveys a lot in a few words, students learn to extract meaning from concise passages.

- Patience and Reflection: Writing haiku requires careful thought and reflection. Students learn to be patient and thoughtful in their creative process, considering the impact of each word on the overall poem.

- Connection to Nature: Haiku’s emphasis on nature can foster a love and appreciation for the outdoors. It encourages students to notice the beauty in simple things and promotes environmental awareness.

- Collaboration and Sharing: Haiku can be a collaborative activity, where children work together to create a series of poems or a haiku sequence. Sharing their work with peers can build confidence and communication skills (see sample lesson plan below).

- Ease of Entry: Because haiku is short, it’s accessible to all students, even reluctant writers.

In all of these ways, teaching haiku poetry to students goes far beyond the poetic form itself. It provides a holistic learning experience that encompasses language skills, creativity, cultural awareness, and emotional expression.

All of this from seventeen syllables!

Using Haiku in the Classroom

Haiku is perfect for “writing across the curriculum”. Often, we think students have to write essays or paragraphs, but poetry, and in particular haiku, offers a great opportunity for students to write very short form pieces that don’t arouse writing resistance.

Who Am I? Poem

Haiku is a fun way to write a “who am I?” poem. Describe something in the poem, and have the reader guess what it is.

Here are three examples. Can you figure them out?

Pot of gold awaits

Colors bending down to earth

Gift after the rain

Falling softly down

White against the stillness chill –

Winter’s gift of peace

Ship of the desert

Tan against the burning sand

Hooves and hump and lashes long

Have students create these for any content.

- Can you have students write them about a number or set of numbers?

- Can you have students write them about figurative language or story elements?

- Can you have students write them about people or events?

Sample Haiku Science Lesson Plan

Here’s a quick fifteen-minute science haiku lesson plan you can use. I created it to address a 5th grade standard, but you could adjust it to any grade level standard.

Task: Haiku Creation

Objective: Writing a haiku poem that addresses NGSS 5-ESS2-2

The Standard:

Describe and graph the amounts and percentages of water and fresh water in various reservoirs to provide

evidence about the distribution of water on Earth. [Assessment Boundary: Assessment is limited to oceans, lakes, rivers, glaciers, ground water, and polar ice caps, and does not include the atmosphere.]

Nearly all of Earth’s available water is in the ocean. Most fresh water is in glaciers or underground; only a tiny fraction is in streams, lakes, wetlands, and the atmosphere. (5-ESS2-2).

Haiku can be part of the description required in the standard, and it can augment the graph students create.

For this lesson, students should be familiar with the idea that most of the Earth’s water is in the oceans.

Instructions:

1. Form a group of 3 students.

2. Assign each student a role:

– Writer: Responsible for writing the haiku poem. The writer should be drafting the poem as the researcher is working, sharing ideas with each other.

– Researcher: Responsible for gathering information about the standard.

– Presenter: Responsible for writing the haiku in an attractive way that reflects the poem. This may or may not include art. The presenter should be paying careful attention to the work of the other two students.

3. The writer will write the haiku poem, incorporating information about the standard.

4. The researcher will gather information about the standard, ensuring the haiku reflects the standard.

5. The presenter will write out the haiku, ensuring they write neatly and add something that reflects the standard (a drawing, a color, a map, etc.).

6. Each student will have approximately 4 minutes to complete their task.

7. Once the tasks are complete, the group will come together to check over their final work.

8. Optional: The group will present their haiku to the class, and each member will share their role in the creation of the haiku.

Time: Approximately 15 minutes (without class presentation).

Note: The teacher should monitor the group’s participation, ensuring each member contributes to the task. After the activity, the teacher should facilitate a discussion about what the students learned and provide constructive feedback on their collaboration and individual contributions.

Quick Idea for Incorporating Haiku

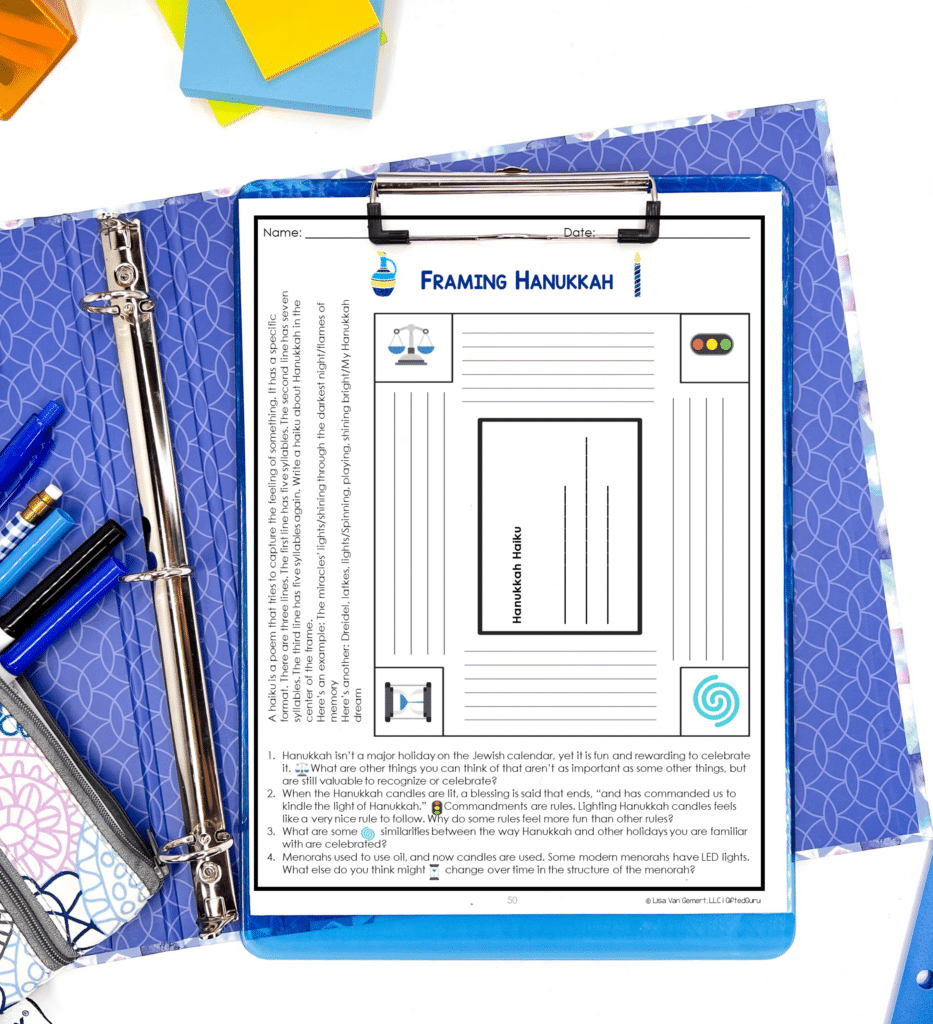

In my Hanukkah lesson plan, I have students write a haiku in the center of a Depth and Complexity frame. As you can see in the image below, I give brief instructions for writing a haiku to the left of the frame. Students then draft their poem in the center of the Depth and Complexity frame.

This is part of a larger Depth & Complexity lesson plan on Hanukkah. You can purchase that entire lesson plan here.

Sample Language Arts Lesson Plan (10th Grade) Using Haiku

In this lesson plan, students work on their mastery of external conflict, using haiku as an innovative way to review the standard.

Objective:

Students will be able to analyze and identify external conflicts in stories and express their understanding through writing a haiku poem.

Assessment:

Students will be assessed through their completion of a haiku poem that reflects the type or types of external conflict in the story.

Key Points:

– Define and differentiate between internal and external conflicts

– Identify different types of external conflicts (e.g., person vs. person, person vs. nature, person vs. society)

– Analyze examples of external conflicts in stories

– Understand the impact of external conflicts on the plot and characters

– Express understanding through writing a haiku poem

Opening:

Engage students by showing them a short video clip or reading a short story that has an obvious external conflict. Ask students to identify the conflict and discuss how it impacts the story. Use this as a hook to introduce the concept of external conflicts in stories. Consider using a fairy tale (one more standard reviewed!) such as

Introduction to New Material:

Remind students of the difference between internal and external conflicts, emphasizing that external conflicts involve a struggle between a character and an outside force. Ask them to list different types of external conflicts and discuss their impact on the story and characters. Anticipate a common misconception where students may confuse internal conflicts with external conflicts.

Independent Practice:

Set behavioral expectations for the work time and assign students to choose a story of their choice and c write a haiku poem that reflects the type or types of external conflict in the story. The poem should capture the essence of the conflict in a concise and evocative manner.

Closing:

Have students share their haiku poems with the class and discuss their choices in relation to the external conflicts in their chosen stories.

Differentiation:

- High ability: Give them the added constraint of a particular type of external conflict, like man v. machine.

- Students in need of support: Give them a word bank of possible words associated with external conflict.

Standards Addressed:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.9-10.3

Analyze how complex characters (e.g., those with multiple or conflicting motivations) develop over the course of a text, interact with other characters, and advance the plot or develop the theme.CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.9-10.5

Analyze how an author’s choices concerning how to structure a text, order events within it (e.g., parallel plots), and manipulate time (e.g., pacing, flashbacks) create such effects as mystery, tension, or surprise.

Some More Background on Haiku Poetry

Matsuo Bashō was a famous Japanese poet who died in 1694. If you work with haiku at all, his name will come up again and again.

His poems still survive and are studied and enjoyed today. Here are two examples, both of which are accessible to even very young students:

An ancient pond

A frog jumps in

The splash of water

Now then, let’s go out

To enjoy the snow…until

I slip and fall

More Resources on Haiku

If you’d like to learn more about haiku (or you have a student who does), here are some places to check out:

- The library on the campus of California State University at Sacramento houses theworld’s largest public collection of haiku outside of Japan. You can search the site tofind haiku poems from certain time periods or about certain topics. This is a grown-upsite, but if you’re really interested in haiku, it’s the best there is.

- The Haiku Society of America makes their journal Frogpond available online.

Haiku Books for Children and Youth

There are loads of haiku books, and it can be hard to find ones that follow the haiku pattern while being engaging for young readers.

Some of my favorites include (affiliate links):

For younger readers:

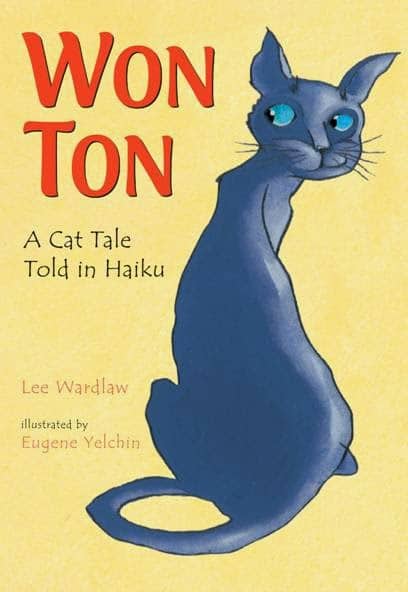

- Won Ton by Lee Wardlaw

- Don’t Step on the Sky by Miriam Chaikin and Hiroe Nakata

- Guyku: A Year of Haiku for Boys by Bob Raczka

- Haiku Baby (board book) by Betsy Snyder

- Guess Who Haiku by Deanna Caswell

- One Leaf Rides the Wind by Celeste Mannis

- H is For Haiku: A Treasury of Haiku From A to Z by Sydell Rosenberg

For older readers:

- There is also a whole series of Horror Haiku books (think werewolves and

zombies) by Ryan Mecum - The Penguin Book of Haiku edited by Adam Kern

- The Haiku Handbook -25th Anniversary Edition: How to Write, Teach, and

Appreciate Haiku by William J. Higginson - The Essential Haiku: Versions of Basho, Buson, & Issa edited and

translated by Robert Hass

You can see all of my book lists for kids on my Amazon page.

Final Words about Haiku in the Classroom

Chalk dust in the air,

Whispers of pencils on desks,

Learning’s silent hum.

School is the perfect place for haiku! I hope these resources have been helpful in giving you some ideas about how and why to use haiku in your classroom.